Scientists at NIAID are progressing toward a faster, more practical way to screen people and animals for prion diseases, which have baffled researchers for decades.

Background

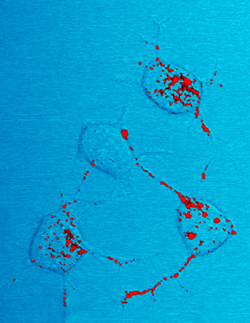

Prion diseases, also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), are difficult to diagnose, untreatable, and ultimately fatal. Normally, prion protein molecules exist harmlessly in every mammal, but for reasons not fully understood, these protein molecules sometimes develop abnormalities and gather in clusters. Accumulation of these abnormal prion protein clusters is associated with tissue damage that leaves microscopic sponge-like holes in the brain.

Prion diseases include sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (CJD) and variant CJD in humans; scrapie in sheep; chronic wasting disease in deer, elk, and moose; and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as mad cow disease, in cattle.

Because animals and people can be infected for years before clinical signs or symptoms appear, scientists have tried to develop a rapid and sensitive screening tool to detect prion diseases in blood. Such a test would help prevent the spread of prion diseases among and between species. Of particular concern is the known transmission of variant CJD via blood transfusions.

At present, the best diagnostic tests for CJD use cerebral spinal fluid or actual brain tissue as test samples; neither is easily obtained. Moreover, the current spinal fluid-based tests are not fully sensitive or specific for CJD infections.

“A blood test would be much better for the patient or animal,” says Byron Caughey, Ph.D., a senior investigator of prion diseases at the NIAID Rocky Mountain Laboratories. “And results should be available in hours instead of weeks. That’s the ideal situation.”

Research Advance

An NIAID research team led by Dr. Caughey has made several advances toward a blood test for prion diseases: one that is fast, accurate, and simple-to-use. His group’s latest test (link is external), developed by Christina Orrú, Ph.D., is called enhanced quaking-induced protein conversion (eQuIC). This approach uses an antibody to isolate abnormal prion protein from blood plasma and an amplification reaction to enhance detection.

In studies using brain tissue infected with variant CJD and then diluted into human plasma, eQuIC detected abnormal prion protein with a sensitivity that is 10,000 times greater than previously described tests for variant CJD. The blood test also accurately differentiated between 13 hamsters infected with scrapie, four of which were in early pre-clinical phases of infection, and 11 uninfected hamsters.

Significance

As a screening tool, eQuIC might have many users, including blood banks, hospitals, livestock operations, and even rendering plants, says Dr. Caughey.

“By detecting infectious prions in tissues, foods, medical devices, and the environment, you could reduce the spread of these diseases. We think there may be many applications in medicine, agriculture, wildlife biology, and research,” he explains.

The general approach of the eQuIC assay could extend to the diagnosis of other similar neurodegenerative protein diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s diseases. But much more research needs to be done.

Next Steps

Dr. Caughey hopes to apply eQuIC to additional prion diseases. Through collaborations with prion diagnostic groups around the world, he hopes to establish eQuIC, or its next generation, as a cost-effective diagnostic tool for users such as physicians in the United Kingdom, sheep ranchers in the United States, beef importers in Japan, and elk farmers in Canada.

He mentions that each year sporadic CJD kills on average one of every 1 million people around the world. An assay such as eQuIC could help determine the overall infection rate in the population and the risks of transmissions to others.

eQuIC also could improve prospects for treating prion diseases. “If you have any hope of treatment at all,” says Dr. Caughey, “then you would want to know as soon as possible what disease you’re dealing with, before irreversible brain damage occurs. With earlier diagnoses and improved therapies, prion disease may not have to be a death sentence.”

References

Orru C et al. Prion disease blood test using immunoprecipitation and improved quaking-induced conversion. mBio. DOI: 10.1128/mBIo.00078-11 (2011).

Wilham J et al. Rapid end-point quantitation of prion seeding activity with sensitivity comparable to bioassays. PLoS Pathogens 6(12): e1001217. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001217 (2010).

Atarashi R et al. Simplified ultrasensitive prion detection by recombinant PrP conversion with shaking. Nat Methods. 3:2011-2012. DOI:10.1038/nmeth0308-211 (2008)

Atarashi R et al. Ultrasensitive detection of scrapie prion protein using seeded conversion of recombinant prion protein. Nat Methods.4:645-50. DOI: 10.1038/nmeth1066 (2007)

Source: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/blood-test-could-detect-prion

Postado por David Araripe

Enviado por Kyria Santiago

Background

Prion diseases, also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), are difficult to diagnose, untreatable, and ultimately fatal. Normally, prion protein molecules exist harmlessly in every mammal, but for reasons not fully understood, these protein molecules sometimes develop abnormalities and gather in clusters. Accumulation of these abnormal prion protein clusters is associated with tissue damage that leaves microscopic sponge-like holes in the brain.

Prion diseases include sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (CJD) and variant CJD in humans; scrapie in sheep; chronic wasting disease in deer, elk, and moose; and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as mad cow disease, in cattle.

Because animals and people can be infected for years before clinical signs or symptoms appear, scientists have tried to develop a rapid and sensitive screening tool to detect prion diseases in blood. Such a test would help prevent the spread of prion diseases among and between species. Of particular concern is the known transmission of variant CJD via blood transfusions.

At present, the best diagnostic tests for CJD use cerebral spinal fluid or actual brain tissue as test samples; neither is easily obtained. Moreover, the current spinal fluid-based tests are not fully sensitive or specific for CJD infections.

“A blood test would be much better for the patient or animal,” says Byron Caughey, Ph.D., a senior investigator of prion diseases at the NIAID Rocky Mountain Laboratories. “And results should be available in hours instead of weeks. That’s the ideal situation.”

Research Advance

An NIAID research team led by Dr. Caughey has made several advances toward a blood test for prion diseases: one that is fast, accurate, and simple-to-use. His group’s latest test (link is external), developed by Christina Orrú, Ph.D., is called enhanced quaking-induced protein conversion (eQuIC). This approach uses an antibody to isolate abnormal prion protein from blood plasma and an amplification reaction to enhance detection.

In studies using brain tissue infected with variant CJD and then diluted into human plasma, eQuIC detected abnormal prion protein with a sensitivity that is 10,000 times greater than previously described tests for variant CJD. The blood test also accurately differentiated between 13 hamsters infected with scrapie, four of which were in early pre-clinical phases of infection, and 11 uninfected hamsters.

Significance

As a screening tool, eQuIC might have many users, including blood banks, hospitals, livestock operations, and even rendering plants, says Dr. Caughey.

“By detecting infectious prions in tissues, foods, medical devices, and the environment, you could reduce the spread of these diseases. We think there may be many applications in medicine, agriculture, wildlife biology, and research,” he explains.

The general approach of the eQuIC assay could extend to the diagnosis of other similar neurodegenerative protein diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s diseases. But much more research needs to be done.

Next Steps

Dr. Caughey hopes to apply eQuIC to additional prion diseases. Through collaborations with prion diagnostic groups around the world, he hopes to establish eQuIC, or its next generation, as a cost-effective diagnostic tool for users such as physicians in the United Kingdom, sheep ranchers in the United States, beef importers in Japan, and elk farmers in Canada.

He mentions that each year sporadic CJD kills on average one of every 1 million people around the world. An assay such as eQuIC could help determine the overall infection rate in the population and the risks of transmissions to others.

eQuIC also could improve prospects for treating prion diseases. “If you have any hope of treatment at all,” says Dr. Caughey, “then you would want to know as soon as possible what disease you’re dealing with, before irreversible brain damage occurs. With earlier diagnoses and improved therapies, prion disease may not have to be a death sentence.”

References

Orru C et al. Prion disease blood test using immunoprecipitation and improved quaking-induced conversion. mBio. DOI: 10.1128/mBIo.00078-11 (2011).

Wilham J et al. Rapid end-point quantitation of prion seeding activity with sensitivity comparable to bioassays. PLoS Pathogens 6(12): e1001217. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001217 (2010).

Atarashi R et al. Simplified ultrasensitive prion detection by recombinant PrP conversion with shaking. Nat Methods. 3:2011-2012. DOI:10.1038/nmeth0308-211 (2008)

Atarashi R et al. Ultrasensitive detection of scrapie prion protein using seeded conversion of recombinant prion protein. Nat Methods.4:645-50. DOI: 10.1038/nmeth1066 (2007)

Source: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/blood-test-could-detect-prion

Postado por David Araripe

Enviado por Kyria Santiago

Comentários

Postar um comentário